Over the years having worked in consulting and research I have been sent countless portfolios for opinion. Virtually all portfolios have followed a pre-defined asset allocation aligned to a specific risk profile but occasionally that is where the alignment ends. This is because the investments selected bear little to no relationship with their desired characteristics or asset class and the final portfolio ends up with risks and/or inefficiencies that may present more downside than expected or intended. This article touches on some of the more common and extreme examples that will hopefully be helpful in assessing your own portfolios.

Faux Pas 1 – Using Geared funds in Balanced Portfolios

This faux pas doesn’t just apply to “balanced” funds and applies to all portfolios where there is a significant defensive allocation to bonds and cash. The one exception is where cash is used for liquidity purposes as opposed to its otherwise defensive income characteristics.

From an asset allocation perspective, holding geared equity funds is the equivalent of holding an equity position of more than 100%, may be potentially 200%, plus a bond allocation that is negative such that it brings the net equity position back to 100%.

Having a negative bond allocation from gearing alongside the usual positive allocation of a balanced fund, not only may reduce the bond allocation to less than desired, it is also inefficient as the cost of borrowing is likely to be higher than the return on the bond allocation which is often dominated by low risk government bonds. If the bond allocation is cancelled by the geared allocation, the expected return on the net zero bond allocation may be negative!

For example, let’s say a 50% growth Asset Allocation portfolio has an allocation of investments that are 20% Cash, 30% Bonds, 20% Geared Equity Fund, 30% Equities. If the Geared Equity fund borrows $1 at 3.5%pa for every $1 invested (i.e. Loan to Value ratio of 50%), then the resulting asset allocation becomes:

- Cash +20%

- Bonds +30%

- Cash/Bond allocation from Geared Equity Fund -20%

- Total Cash/Bonds +30%

- Equity allocation in Geared Equity Fund +40% (Two times 20%)

- Equities +30%

- Total Equities +70%

This results in a 70% growth asset portfolio and not the desired 50% hence creating greater risk than intended.

In terms of expected returns, if we assume a 2.5% long run expected return on Cash and 3% on Bonds, the expected return on the Cash/Bond allocation becomes:

(20%*2.5% + 30%*3% + -20%*3.5%)/30% = 2.3% … less than the expected return of Cash and Bonds!

Faux Pas 2 – Allocating High Yield Bond Funds to Defensive Bonds

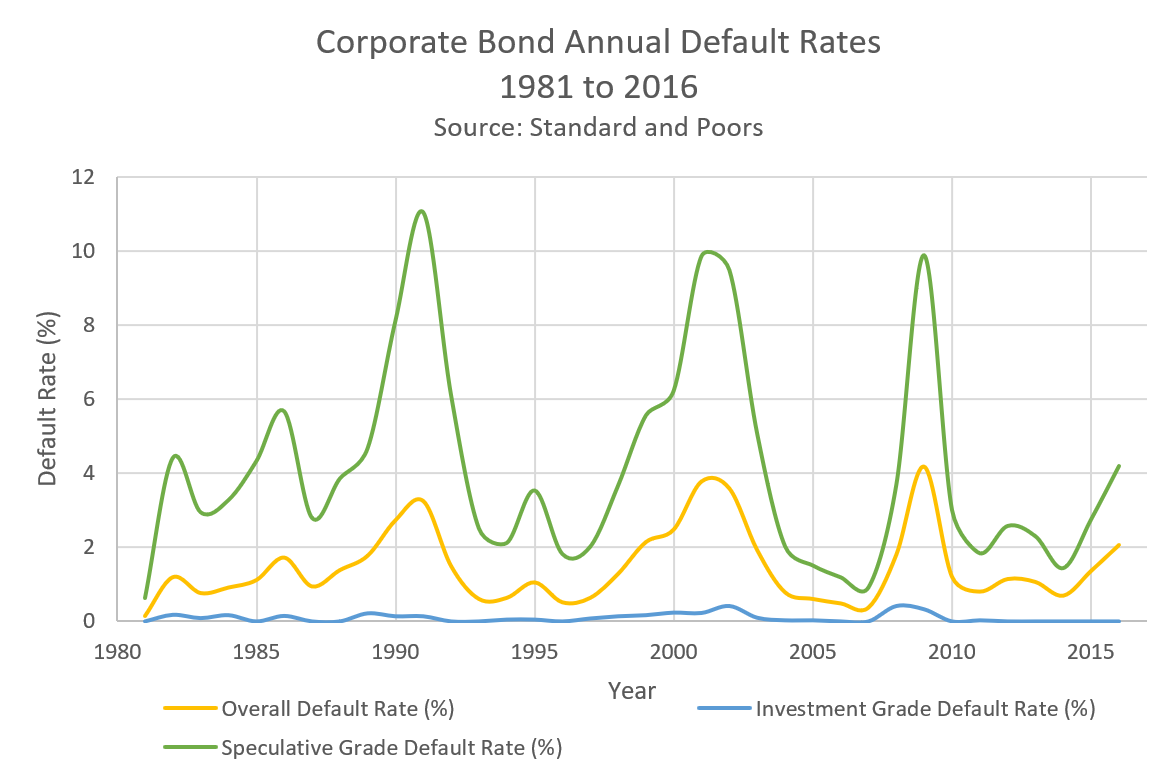

We don’t often refer to high yield bonds as junk bonds nowadays but either way, below investment grade bonds, by definition, are not defensive. Chart 1 shows the comparison of default rates between investment grade and speculative Grade (non-investment grade), and whilst investment grade bonds have very few defaults, Speculative Grade bonds frequently have defaults of more than 1% to 2%, including almost 10% default rate as a result of the GFC in 2009.

Chart 1

From a performance perspective, the Bloomberg Barclays Global High Yield index, which broadly represents Global non-investment grade bonds, can often show equity like characteristics…usually in a down market. For example, during the worst performing calendar year of the GFC, this High Yield index (hedged to Australian dollars) returned negative 27.6% which was lower than the MSCI World which returned a negative 24.9%.

Given the dominance of equity risk on multi-asset class portfolios, one of the roles of the defensive asset class should be to cushion equity market risk. Unfortunately, during stressed equity markets, and not just the GFC, high yield bonds generally become highly correlated with equity markets and perform the complete opposite of what you would hope from a defensive investment. As Chart 1 shows, the worst years since 1981 for of Speculative Grade defaults were 1991, 2001, 2002, and 2009 … all associated with recessions and poor or stressed equity markets (Recession, Tech Wreck, and GFC).

Faux Pas 3 – Market Neutral Funds in Equity Asset Class

In terms of the effect on the portfolio’s asset allocation, this Faux Pas is the complete opposite of using Geared funds. That said, Market Neutral funds are a type of Geared Share fund, except instead of borrowing cash to invest, the market neutral fund borrows stock, but the same amount that it buys. This results is a net allocation to equities that equals zero. The fact that a market neutral fund, may implement their strategy in the Australian equities market (or US, or Asia, et al.) doesn’t make it representative of the Australian equities asset class. The asset allocation decision is expected to be a “long” market allocation decision (sometimes know as a beta decision).

Because the market neutral fund generally has a net allocation to its underlying asset class of zero, the return characteristics are more likely to resemble Cash plus Alpha, where Alpha represents the excess return of the fund’s long positions minus it’s short positions. If Alpha is greater than the fees charged then the return is likely to be Cash plus Alpha minus fees, otherwise the return will be less than Cash minus fees.

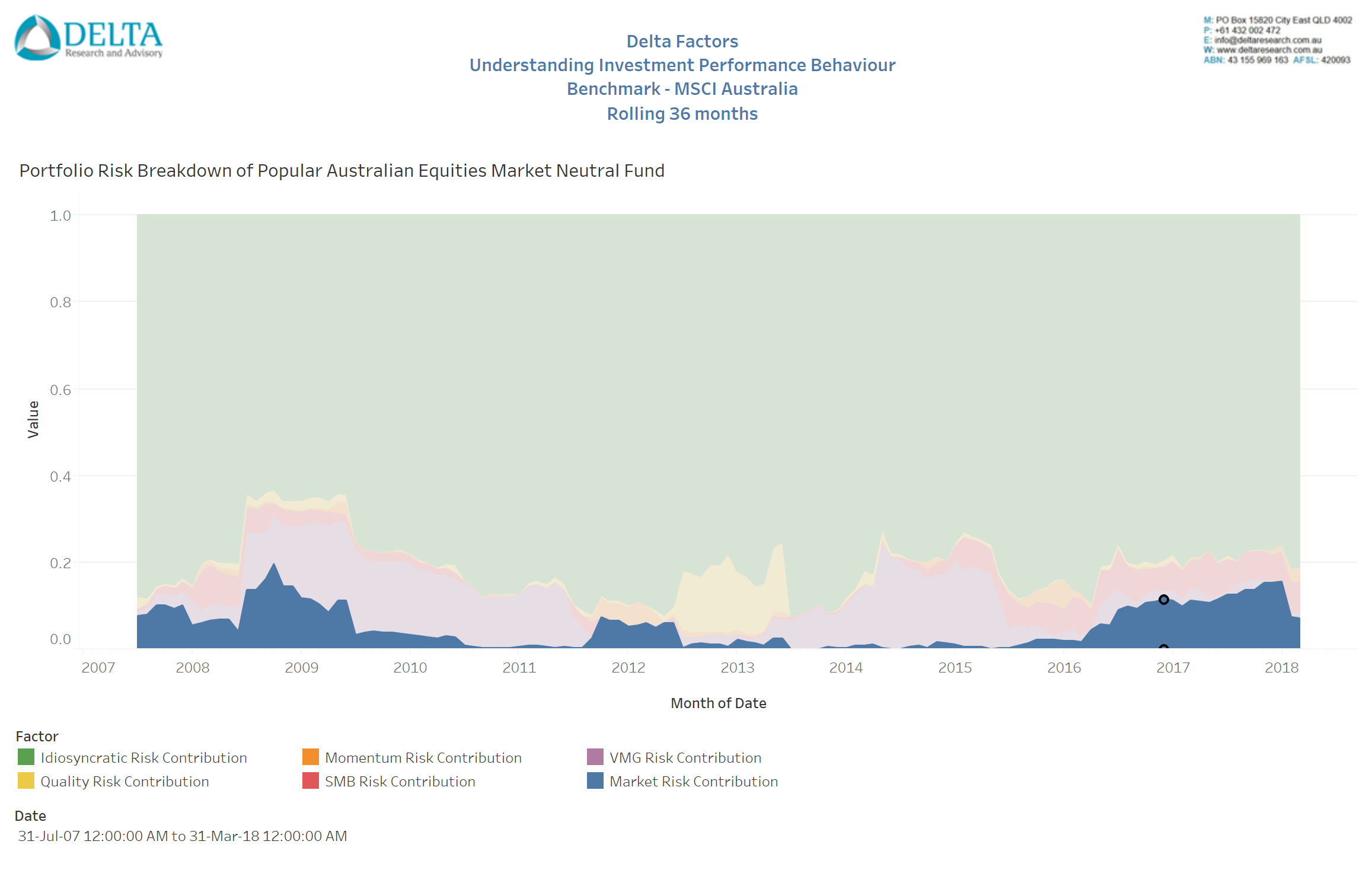

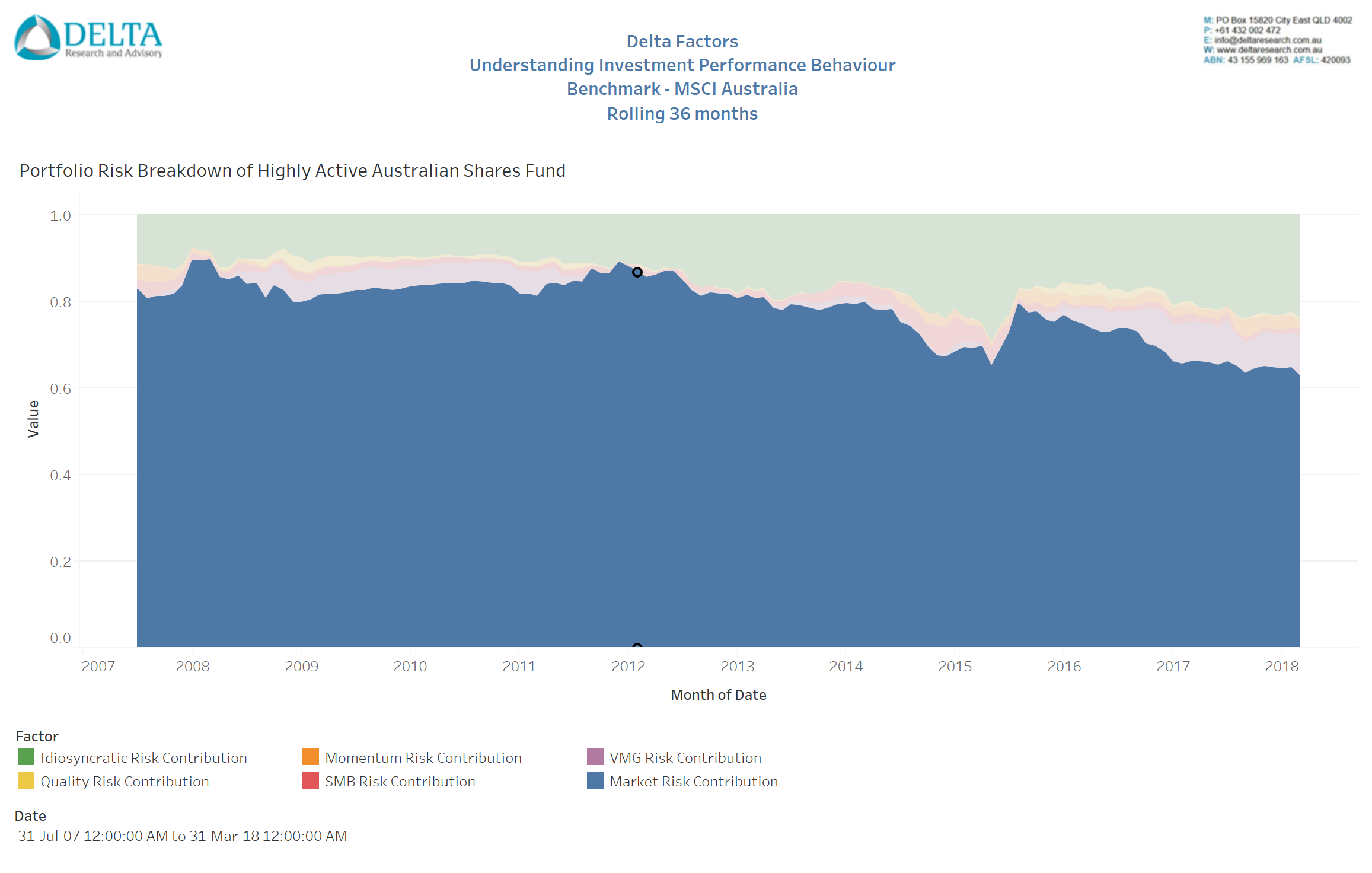

Charts 2 and 3 breaks up the risk of an Australian Equities focused market neutral fund and popular traditional active Australian equities fund show the proportion of total portfolio risk due to the Australian Market. As can be seen the Market Neutral fund bears has little to no Australian equities market (as defined by MSCI Australia) risk compared to the highly active long only Australian equities fund.

Chart 2 – Australian Equities Market Neutral Fund

Chart 3 – Popular Highly Active Australian Equities Fund

Because of this lack of relationship between the Market Neutral fund and the Australian equities market (or any market), the Market Neutral fund should generally be classified as an “Alternative”, as its Cash and Alpha performance outcome should be uncorrelated to Australian equities.

Final Thoughts

Having investments that don’t completely reflect their respective asset class is not always a problem. They may be playing specific roles to mitigate or capture desired risks. A high yield bond fund as part of the bond portfolio may be absolutely fine, as long as that bond portfolio does not play a purely defensive role to the equities portfolio and is positioned more as a higher income generator. A geared equities fund may be fine for a client, particularly for a high growth investor who has no long term defensive allocation in their recommended portfolio, or perhaps where the bond allocation is appropriately of the higher return/risk variety and therefore potentially earning more than the cost of gearing.

The key point to all of this is …. we are aware of the requirement to “know your product” but some of the riskier or more complex products will typically require a lot more analysis and understanding than the asset class source of their returns.